EXHIBIT: The Winslow Homer Studio – A History

The Importance of Place:

The Structural Evolution and History of

Winslow Homer’s Studio

1883-2013

by Caroline Willauer, August 2014

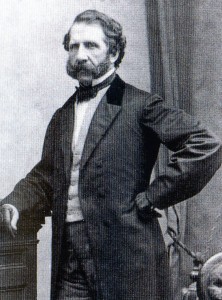

Winslow Homer famously spent the last few decades of his life in a humble wooden cottage on the rocky coast of Maine. Unlike other artists of the time who also spent summers at artist colonies or remote cottages, Homer chose to stay in his studio through the bitter cold Maine winters. The lifelong bachelor’s extended observation of the sea, during every season of the year, is attributed to his artistic accomplishment. The powerful seascapes and watercolors that he painted during this time remain some of his best and most well known works.

Just as Thomas Denenberg said Homer is “…viewed as a painter who exemplifies those quintessentially American qualities of self reliance, courage, independence, and masculinity,” Mainers are often described in a similar vein. It is no coincidence that scholars see the Boston-born Homer’s time in his studio in Maine as a major factor in his maturation as an artist. Any sketches or quick watercolors he made during his many travels were brought back to the studio for further production, sometimes into more advanced oils. Since Homer’s death, his studio has been used and enjoyed by younger generations in varying capacities, all which sought to preserve the spirit of Uncle Winslow’s way of life. For over a century the simple structure has endured many a nor’ easterly wind, renovation, curious visitor, and dinner party, all the while perpetuating the myth of how the intensely private Homer spent his days.

Much of what we know about Winslow Homer comes from the many letters he wrote to friends and family over the years, their letters to him, and oral tradition passed down through the Homer family. The simple configuration of the studio also reveals details about his lifestyle, especially compared to his brother’s spacious home next door, aptly named The Ark. While Charles Savage hosted parties and employed live-in staff, Winslow preferred to live alone in his minimally furnished, two room clapboard studio, which was originally an extant building for The Ark’s carriage house (page 18, figure 1).

The first floor included an entryway, main room, and “sleeping room,” as the owner referred to the small space similar in size to the entryway . In the main room was a brick fireplace which heated the building and where Winslow cooked his meals using a large pot attached to the wall by a metal arm with hinges. On the western wall there was originally an exterior shed-roofed addition, which possibly held the privy . Otherwise the first floor was one large space with two nooks for the entryway and sleeping area.

The first floor included an entryway, main room, and “sleeping room,” as the owner referred to the small space similar in size to the entryway . In the main room was a brick fireplace which heated the building and where Winslow cooked his meals using a large pot attached to the wall by a metal arm with hinges. On the western wall there was originally an exterior shed-roofed addition, which possibly held the privy . Otherwise the first floor was one large space with two nooks for the entryway and sleeping area.

Similarly, the second floor was one open space but mostly used for storage, and opened to a south-facing piazza overlooking the ocean. The side of the piazza facing the Ark had a latticed wall clearly meant for privacy. “Great transitional figures in art and culture from sentimental culture in 1800s to modernists were all about the individual,” Denenberg notes, and while Homer was “someone who needed community, family, hearth & home, and a place to be who he was,” that didn’t mean he wanted to be spending all his days socializing . The north side of the studio that faced the road had just one upstairs window, which the owner often covered over – again, for privacy – this time from curious members of the public. By the time he moved to Maine, Homer had been revered enough as an illustrator to be asked to cover President Lincoln’s second inauguration for Harper’s Weekly, and there were some that hoped to catch of glimpse of him working in Prouts . Homer was a friendly and generous man to those he chose to have relations with, but he had no time for tourists or fans.

Many viewed Homer’s move from the cultural center that was New York City to the relatively uninhabited Maine coast as deliberate isolation, which he did not argue. Homer preferred to do his work without being surrounded and influenced by other artists, but was by no means isolated as he received several daily papers: The New York Times and The London Standard, among others. Professor Emeritus of the History of American Art James F. O’Gorman compares Homer’s chosen lifestyle to that of Henry David Thoreau and Charles Keeler, both writers of the time who symbolized the idea of simple living and closeness to nature in the emerging Arts & Crafts movement .

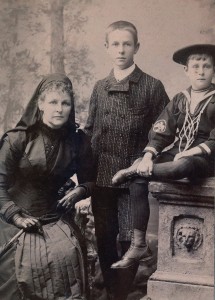

If Homer was not isolated because he kept up with world news, he also was not alone most of the time – indeed the move to Prouts had been mostly motivated by family ties. In the early years Homer would visit his sister-in-law daily, attend a few of his brother’s dinner parties, and get along with the local fishermen. When he was not traveling with Charles Savage to fish in the Adirondacks or spending a few weeks in the Bahamas for a change of pace, Homer enjoyed spending lots of time with his family at Prouts. Around the turn of the century Charles Savage Homer Senior required more attention, and Homer took over as caretaker and companion. The studio provided a quiet sanctuary; a place that was his to ponder the meaning of life and observe the crashing waves.

If Homer was not isolated because he kept up with world news, he also was not alone most of the time – indeed the move to Prouts had been mostly motivated by family ties. In the early years Homer would visit his sister-in-law daily, attend a few of his brother’s dinner parties, and get along with the local fishermen. When he was not traveling with Charles Savage to fish in the Adirondacks or spending a few weeks in the Bahamas for a change of pace, Homer enjoyed spending lots of time with his family at Prouts. Around the turn of the century Charles Savage Homer Senior required more attention, and Homer took over as caretaker and companion. The studio provided a quiet sanctuary; a place that was his to ponder the meaning of life and observe the crashing waves.

The Homer family’s decision to occupy Prouts Neck was partly due to the convenience of having a central gathering place for the family in the summer, and partly a business venture. Arthur Benson, brother of Henrietta Benson Homer and uncle to Winslow Homer, bought all of Montauk Point in 1879 in order to establish a sportsman’s haven and small seasonal community. Homer helped with preliminary sketches for this grand plan, which involved hiring F. L. Olmsted as landscape designer and Stanford White as architect . The final product was named the Montauk Association of Easthampton and would go on to become the wildly successful summer enclave now known as The Hamptons.

Homer’s father, Charles Savage Homer Senior, most likely modeled Prouts after the idea of Easthampton: first buying all of Prouts Neck over the next few years, overseeing the construction of his sons’ cottages, and selling parcels of land to approved individuals later on. Charles Savage Homer Junior built The Ark in 1883, followed by Arthur Benson Homer’s El Rancho in 1882. Just as Arthur Benson had hired Stanford White to be his chief architect, so too did the Homer men choose a chief architect, a John Calvin Stevens. In 1884, when Winslow asked that The Ark’s carriage house and stable be remodeled into a little studio for himself, it was Stevens who drew up the plans according to the artist’s particular specifications (page 19, figures 3 and 4).

Homer’s father, Charles Savage Homer Senior, most likely modeled Prouts after the idea of Easthampton: first buying all of Prouts Neck over the next few years, overseeing the construction of his sons’ cottages, and selling parcels of land to approved individuals later on. Charles Savage Homer Junior built The Ark in 1883, followed by Arthur Benson Homer’s El Rancho in 1882. Just as Arthur Benson had hired Stanford White to be his chief architect, so too did the Homer men choose a chief architect, a John Calvin Stevens. In 1884, when Winslow asked that The Ark’s carriage house and stable be remodeled into a little studio for himself, it was Stevens who drew up the plans according to the artist’s particular specifications (page 19, figures 3 and 4).

Following F. L. Olmsted’s call for simplicity and use of shingle style design, John Calvin Stevens worked with the Homers on developing and building Prouts Neck into a popular summer community . Homer and Stevens got on well; both were proponents of the simpler lifestyle, individualism, and self-sufficiency. After the studio, Stevens went on to design another house for Homer and 13 other homes on Prouts Neck. Homer considered Stevens and himself ‘brother artists’ and their relationship continued the rest of their lives . The young architect became known for the Shingle Style cottages he designed around New England; primarily Maine, where more simple values and closeness to nature are encouraged in life as well as architecture.

Few realize that Homer considered himself a businessman first, and artist second. Charles Savage Homer Junior financed the addition of a painting room for his younger brother in 1890 . Never short on wit, the artist referred to this room as his ‘factory,’ which reveals his awareness of art as his livelihood rather than hobby. Andy Warhol called his studio “The Factory” as well, but because the building had actually been a former hat factory. “Homer was a businessman – producing work to sell. Not any sort of bohemian. [He] considered his business to be his art,” Portland Museum of Art docent Ted Connolly argued in a 2011 podcast . The family-oriented bachelor also oversaw real estate transactions for the Homer family during the winter months and while they were away; in this way he was very much a man-about-town and known in the community.

There were several additions to the studio during Homer’s many decades living there that remain undocumented except for photographic evidence. Sometime between the construction of the painting room in 1890 and a photograph taken by biographer William Howe Downes in 1910, the small shed-roofed privy had been enclosed in an addition that started next to the chimney and extended beyond the southern side of the studio. The result was a one story, rectangular box built a few feet off the ground which provided a small entryway on the western side of the building and a larger space for a proper bathroom (page 20, figure 5). On the opposite wall above the eastern entryway, there is evidence of a ladder attached to the side of the roof, as if Homer sometimes climbed from the piazza to the top of the mansard for a better view of the ocean (page 24, figure 11).

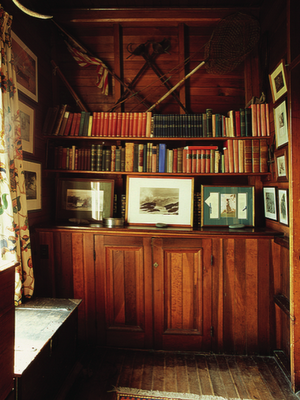

Homer passed away in his studio in 1910, most likely as he lay on his long bench (page 26, figure 16). Shortly after Uncle Winslow’s death, his brother and heir Charles Savage Homer Junior furnished the first floor to make it look and be more livable . Charles Savage already had a comfortably large home next door to the studio, so not much is known about his use of the studio beyond upkeep and interior décor. The eldest Homer’s decision to add furnishings that his brother did not have for the purpose of making the space look lived in by the artist is an ironic part of the studio’s history and the beginning of the mythology of Homer’s studio. Several artifacts that belonged to Winslow do stay – a ship’s wheel, sextant, watercolor palette and brushes, foul weather gear hat, tip-top table, and long bench, among other small items – but the overall appearance of the interior no longer accurately reflects how the artist used the space (pages 23, 26, and 27).

Homer passed away in his studio in 1910, most likely as he lay on his long bench (page 26, figure 16). Shortly after Uncle Winslow’s death, his brother and heir Charles Savage Homer Junior furnished the first floor to make it look and be more livable . Charles Savage already had a comfortably large home next door to the studio, so not much is known about his use of the studio beyond upkeep and interior décor. The eldest Homer’s decision to add furnishings that his brother did not have for the purpose of making the space look lived in by the artist is an ironic part of the studio’s history and the beginning of the mythology of Homer’s studio. Several artifacts that belonged to Winslow do stay – a ship’s wheel, sextant, watercolor palette and brushes, foul weather gear hat, tip-top table, and long bench, among other small items – but the overall appearance of the interior no longer accurately reflects how the artist used the space (pages 23, 26, and 27).

Over the following decade, the exterior went through minor changes in an effort to clean up the studio and make it more usable for the family. A pergola was added and more landscaping put in to the side of the building that faced the road; the idea was to turn it into more of a country house (page 21, figure 6). The studio was originally painted a dark grey with darker trim, but by the time Charles Savage Homer Junior inherited it the trim was white and clapboards a soft green. Around the turn of the century English Colonial Revival had become more in vogue, and white trim was a characteristic of many homes built in this style.

After Charles Savage Homer Junior and his wife Mattie passed away, the studio and any of Uncle Winslow’s belongings went to their nephew, Charles Lowell Homer. Charles Lowell was a charismatic figure who was very active in the Prouts community and who took it upon himself to play a role in shaping popular understanding of his uncle by preserving his memory. This preservation included marketing Homer’s work in galleries in Boston and New York, correspondence with such historically significant institutions as the Bowdoin Archives of American Art, and even staging a major exhibition in the studio in 1936. The exhibition included original works of his art, artifacts, and anything remaining from Homer’s life .

Just afterwards, in 1938-1939, the studio was heavily altered and added onto so it could be better utilized by the growing family as a summer cottage. Arthur Osborne Willauer, the up-and-coming architect of the New York firm Waid & Willauer, is said to have had a hand in designing the additions according to family tradition. A full working kitchen was built off the western side by the bathroom, and a small powder room was added to the eastern entryway. The second floor was divided into two bedrooms and a bathroom, with a small hallway connecting all three rooms at the top of the stairs. Finally the studio had joined the 20th century as a true residence, complete with a kitchen and proper bedrooms which it had lacked during Homer’s time (no pictures available).

After Charles Lowell Homer’s death in 1955, his second wife Doris “Dory” Homer came into the studio, surrounding acreage, any of Homer’s original works the Charles Lowell had not gifted to museums, and several other family homes around the Neck. The entrepreneurial farmer’s daughter was a dental hygienist at the time but following her acquisitions, decided to start real estate business, which exclusively dealt with Prouts Neck properties . In her later years, Dory led many a tour of the studio for Prouts residents and friends who wanted to hear more about the history of the community and the esteemed local artist who lived there. The painting room contained artifacts belonging to Homer and dozens of framed reproductions that Dory and Charles Lowell had collected over the years, arranged accordingly (page 27, figure 18). From 1955 until 1980, Dory owned the studio but maintained her residence elsewhere on the northwest side of Prouts Neck, on Bird’s Nest Lane.

After Charles Lowell Homer’s death in 1955, his second wife Doris “Dory” Homer came into the studio, surrounding acreage, any of Homer’s original works the Charles Lowell had not gifted to museums, and several other family homes around the Neck. The entrepreneurial farmer’s daughter was a dental hygienist at the time but following her acquisitions, decided to start real estate business, which exclusively dealt with Prouts Neck properties . In her later years, Dory led many a tour of the studio for Prouts residents and friends who wanted to hear more about the history of the community and the esteemed local artist who lived there. The painting room contained artifacts belonging to Homer and dozens of framed reproductions that Dory and Charles Lowell had collected over the years, arranged accordingly (page 27, figure 18). From 1955 until 1980, Dory owned the studio but maintained her residence elsewhere on the northwest side of Prouts Neck, on Bird’s Nest Lane.

Charles Lowell Homer had outlived his son-in-law Arthur Osborne Willauer, so Arthur’s sons were next in line to take care of the family properties. Charles Homer “Chip” Willauer, a similarly magnanimous figure as his Uncle Charles had been and unofficial family historian of his generation bought the studio from Dory in 1980. Circumstances ended up that Chip owned the building, while Dory owned the surrounding land.

Chip continued the preservation of the painting room as a gallery, which was also the main feature of his private tours, available by appointment. Art history scholars, distant relatives, and even school groups were welcomed in to see the painting room and if they were lucky, have a brief tour of the rest of the building. At this time Chip lived full time in the studio, so while he was eager to share his family history, it was more a part-time private museum and full time residence than anything else. Neither Dory nor Chip made any major structural changes to the building; their goal was maintenance.

Chip continued the preservation of the painting room as a gallery, which was also the main feature of his private tours, available by appointment. Art history scholars, distant relatives, and even school groups were welcomed in to see the painting room and if they were lucky, have a brief tour of the rest of the building. At this time Chip lived full time in the studio, so while he was eager to share his family history, it was more a part-time private museum and full time residence than anything else. Neither Dory nor Chip made any major structural changes to the building; their goal was maintenance.

By the late 20th century, the painting room had turned into a shrine to Winslow Homer, but under Chip’s ownership doubled as a spacious dining room for entertaining (page 27, figure 18). The interior decorator was originally from Cambridge, just like his Uncle Winslow, who split his time between clients in Maine and Boston. Also like Homer, Chip was the middle son and lifelong bachelor. Both men were family-oriented; however Chip was very social, known for his gatherings. The simple configuration of the studio proved to be wonderful for parties – the main room had a great fireplace and plenty of seating, the painting room could seat 40 people for dinner if necessary, and the kitchen was relatively hidden.

Certain persons rented the studio with Chip’s approval over the years; many were return customers and included prominent architectural historians and scholars . This unique opportunity was a combination of his goal to educate and the reality of waterfront taxes. While renters occupied the main part of the building, Chip would lock the inner door (connecting the painting room and rest of the studio) but leave the back door unlocked for tours. Both Chip and Dory would take people into the painting room, tell stories about Homer’s attempts to keep tourists at bay, and then walk down the lawn to see the rocks which he eternalized in his great seascapes.

Over the past century, the family continued to share their history and pay tribute to Uncle Winslow while physically altering and decorating the studio into something drastically different than its original form. Photos from a 1984 article by Architectural Digest show a well-appointed cottage by the sea filled with family heirlooms and enough furnishings to fill a space twice as large (pages 22 and 23, figures 8, 9, and 10). Winslow Homer’s Studio was not alone in its false historic interpretation – Homer scholar and former curator at the Portland Museum of Art, Thomas Denenberg, noted that this “tends to be a theme in many historic homes,” and happens inadvertently over time . The studio was still exhibited as such, although it was no longer anything close to an artist’s studio, nor did it reflect the simplicity of Homer’s life choices. In essence, the family created a house that never was.

For years the family discussed turning the studio over to the Portland Museum of Art, which not only had more resources to preserve the structure but the ability to share it and Homer’s legacy with a greater audience. One could say the turnover was inevitable, given the historical significance of the building. A press release from the museum described the relationship between Winslow Homer and the Portland Museum of Art as “long-standing and intimate – indeed Homer exhibited at the Museum in 1893 and his legacy runs throughout the history of the institution.” In 2006, Chip Willauer officially sold the studio to the Portland Museum of Art after a long campaign to raise the funds necessary. Thus began a major restoration to return the clapboard house to its original form as Homer had lived in it while adding modern structural elements to strengthen nearly everything from the foundation up.

Not surprisingly, the restoration revealed evidence of many design elements that had not been documented by Homer or the family. The roof no longer had a ladder, stove pipe, or ridge platform, and the piazza was without the original latticework. Several windows and dormers had been moved and/or altered over the years, most likely to accompany interior changes such as upstairs bedrooms. The original elements were added to the studio and recent additions, such as the full kitchen, powder room, and upstairs rooms, removed .

Not surprisingly, the restoration revealed evidence of many design elements that had not been documented by Homer or the family. The roof no longer had a ladder, stove pipe, or ridge platform, and the piazza was without the original latticework. Several windows and dormers had been moved and/or altered over the years, most likely to accompany interior changes such as upstairs bedrooms. The original elements were added to the studio and recent additions, such as the full kitchen, powder room, and upstairs rooms, removed .

Mills Whitaker Architects of Arlington, Massachusetts spearheaded the project and won a historical preservation award in February 2013 for their creativity in restoring the studio to its authentic appearance while also adding reinforcements. John Calvin Steven’s original piazza had never quite been fully self-supporting, so steel reinforced beams were added but hidden between the wood exterior . The foundation was also struggling to hold the weight of the building and especially the fireplace, so the builders took on the very tedious task of adding support to the original foundation without moving the house.

Winslow Homer’s Studio restoration was completed in the fall of 2012 and briefly opened to the public. The Portland Museum of Art and Mills Whitaker Architects spent the better part of a decade researching how the studio was configured when Homer lived and painted in it, and the result is as authentic as anything can be without speaking with Homer himself. The overall effect of the interior is not just the polar opposite of its splendor of previous years, but truly feels like the barren cottage where a small little artist once spent his days cooking over the fireplace and enjoying his own company. The long bench has been moved to a position where Homer would have sat in it, and none of Chip’s décor remains.

On the outside, the studio has been painted to its original muted tones and the elaborate latticework on the piazza has been beautifully restored (page 24, figure 11). The museum has an agreement with the Prouts Neck Association to only open the studio to the public during the summer season, and only for private tours. The Prouts community works hard to keep its privacy and welcomes those who wish to learn more about Winslow Homer, but just as the artist avoided the influx of summer tourists, so too does the community. In the years to come, the studio will hopefully continue to stand the test of time under the ownership of such a dedicated institution and surrounded by staunch protectors of Winslow Homer’s legacy at Prouts. The memorial placard in the protected sanctuary at Prouts Neck underscores the significance of this relationship: “In appreciation of the generosity of Charles Savage Homer, who gave these woods to the people of Prouts Neck, and the genius of his brother Winslow Homer, who with his brush gave Prouts Neck to the world.”

Click here to view the Portland Museum of Art’s LIVE “Studio Cam”

Nice job!